Arabic (page 5)

Intermediate Arabic I (ALMC 331): Culture Module

Bethany Suitor

For my first cultural portfolio this year, I did the “Arabic Calligraphy” module on Khallina.org. It featured calligraphy artists such as eL Seed and Elinor Aishah Holland as well as the meaning behind commonly used phrases in calligraphy. It also explained how to pronounce the emphatic “L” sound found in popular phrases that contain “Allah”, and interesting facts about the Arabic alphabet that I did not know! I had no idea that Arabic was the second most widely used alphabet in the world (behind the Latin alphabet). The Arabic alphabet is used for languages such as: Persian, Ottoman Turkish, Urdu, Pashto, Kurdish, Sindhi, and others! New letters and symbols were added to the original Arabic alphabet to accommodate other languages; hence, the ‘ch’ sound and letter found in Persian that looks like an Arabic “j” but with three dots instead of one, for example.

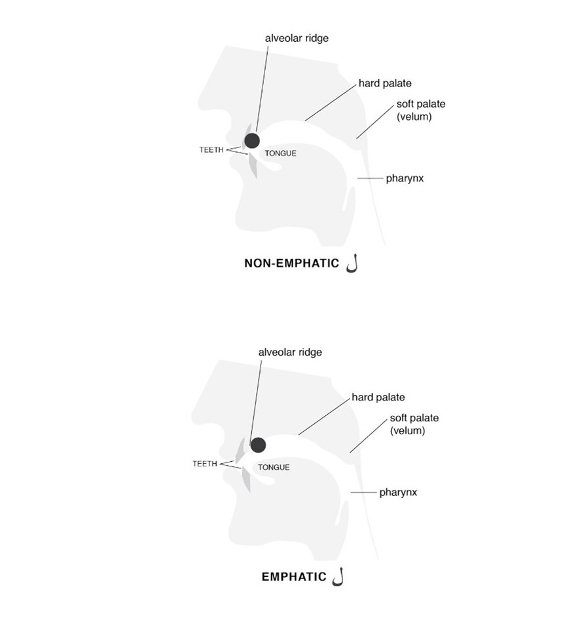

The lesson that I found the most helpful from this module was pronouncing the emphatic “L” found in commonly used phrases containing “Allah”. Because “Allah” is used frequently used in Arabic, I could hear the emphatic “L” but could not pinpoint why my pronunciation of “Allah” was different than other people’s. The module explained that phrases such as: mashalLah, inshalLah, subhaanalLah, alLahu akbar, and aL-Laah 3aleek all have an emphatic “L”, while phrases such as ‘bismillah’ and ‘alhamdulilah’ do not because of the vowel preceding the “L”. It is because these words have a kasra before it, which changes the pronunciation of the following “L”.

I also found new phrases such as ‘subHaanalLah’ and ‘allah 3aleek’ that I never heard before this module. ‘SubHaanalLah’ literally means “Praise be to God” but it is used to express awe at events or objects such as sunsets or the ocean. The module explained that sometimes literal translations are not as useful as knowing how phrases/words are used in cultural context. I think this is a very important (muhim judan) point to make that I will keep with me as I continue my journey learning a new language.

A phrase that I probably should have known the literal translation for but did not, was ‘bismillah’. The module said that it means “in the name of God”. I have heard ‘bismillah’ before, but I never knew what it meant except for some reference to God. Now that I know what it means, I’m surprised I never caught on before. I know that “bi” means “for”, “ism” means “name”, and of course “Allah” means God. Put it all together and it makes sense that it means “in the name of God.”

Some philosophical reflections I had during this module happened when Elinor Aishah Holland and eL Seed spoke about Arabic calligraphy. Elinor Aishah Holland said that calligraphy is the “perfect harmony between control and freedom”. This reminded of ideas conceptualized by Islamic scholars Mawdudi and Qutb. In some of their work, they talk about Islam understanding a person’s need for freedom, but that living within constraints actually makes a person freer than if he’s free to indulge in the very things he wants freedom for. They make the point that when a person is not weighed down by indulgences such as alcohol or gambling, then his soul is free and as this is how God intended him to be, he is happier. Holland’s quote in this module jumped out at me because I too am looking for ‘perfect harmony between control and freedom’.

The second philosophical reflection was when eL Seed said in his Ted Talk that “I think that Arabic script touches your soul before it reaches your eyes. There is a beauty in it that you don’t need to translate.” This also jumped out at me because I frequently feel like I cannot express myself even in my first language, English. I frequently make the argument that logic is better than grammar, and that the soul understands before the intellect can. As they say that most communication is non-verbal, I believe this is because our “instincts” or “soul” pick-up on a person’s subtleties and we can understand a person without proper use of words. I rely a lot on the instincts of the people around me to understand what I’m trying to say rather than my words. I like concepts encapsulating expression that transcends language and ironically, I found something that does in an assignment for a language class: calligraphy.

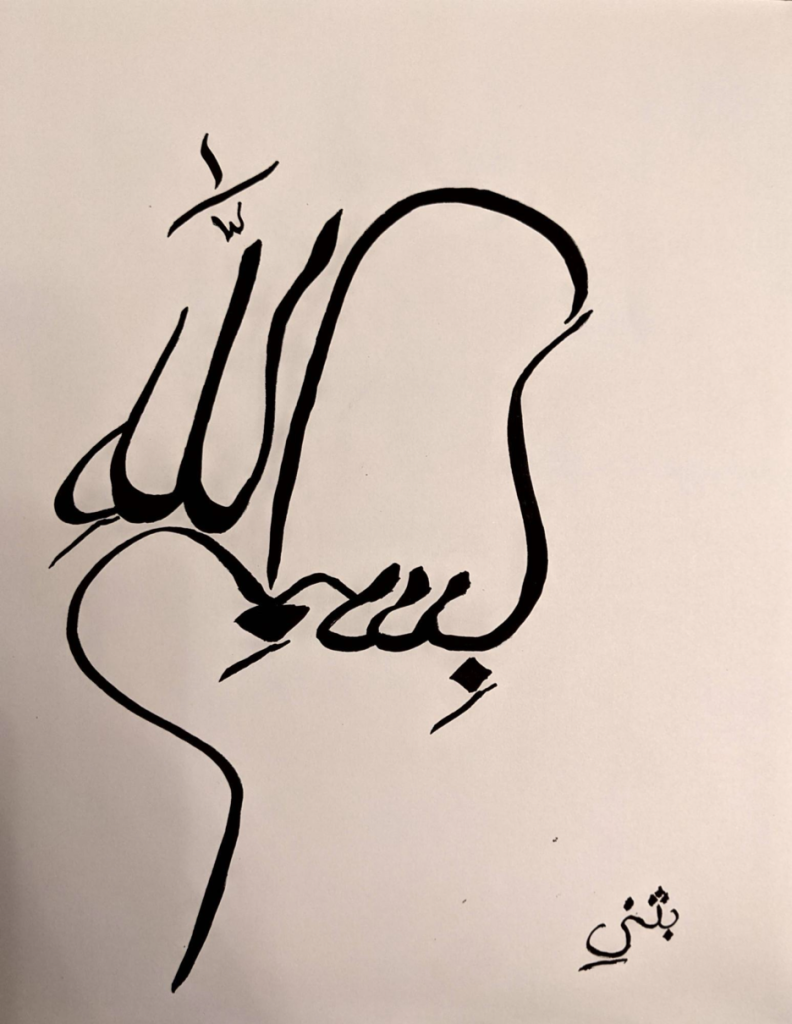

Lastly, I tried calligraphy. In the last step, the module invites you to try calligraphy yourself. I knew mine was going to be amateurish, as it is my first time, but I tried it anyways. I wrote “bismillah” and then signed it in Arabic. It was challenging because when you watch calligraphers, they make lines and letters in one-fell swoop, but I could not do this. I tried, but I was not confident enough and I made lines too thick in some places and made some lines that have ink out of place. Instantly though, I felt that feeling of “harmony between control and freedom”. No two pieces of hand-drawn calligraphy will ever be identical. In this way, calligraphy is free and unmeasurable. It does not matter if the tooth of a ‘ba’ is as long as an alif or if the phrase is read from the bottom to the top, it is free and will not be compared to another piece of calligraphy because of a technicality. Calligraphy is not ruled by precision, yet it is not so free that it is abstract and untidy. Calligraphy is put within the constraints of words and in this way, it becomes the oxymoron of control and freedom. One can twist and elongate or shorten and bend; one can even mix up the order of the words, but they are still that: words. And there is something calming about this. Not to mention, its beauty lies in its uniqueness, its imperfections. It is not defined by details, yet its beauty exists in them. Its imperfections literally make it beautiful.

Bibliography

Khallina.org (Calligraphy Module) https://khallina.org/arabic-calligraphy/

eL Seed’s Calligraffiti on Tunisian Minaret https://www.greenprophet.com/2012/09/tunisias-tallest-minaret-sprayed-with-el-seed-calligraffiti/